I love viewing Black art and consider it an extension of the black American familial/communal experience. No matter how avant-garde or futuristic, there is always something familiar. The themes, patterns, people, and landscapes exist in our collective conscious.

_____________

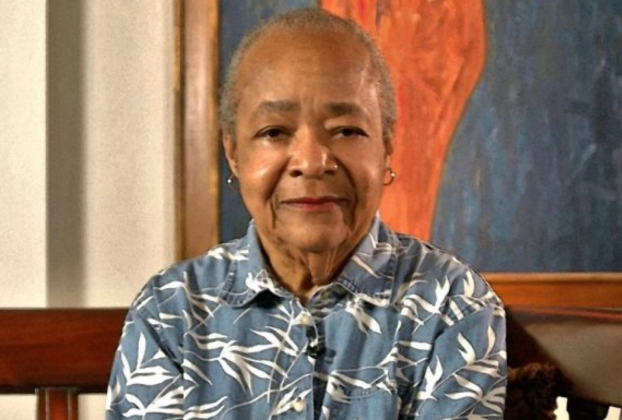

I had never heard of visual artist Samella Lewis until last month when news of her death at age 98 became public. She was a pioneering multi-hyphenate–artist, activist, publisher, art scholar & historian, collector, and educator, –who pursued her creative individuality from a young age.

She was the first Black woman to earn a Ph.D. in Fine Arts & Art History from Ohio State University, after completing her undergraduate studies at both Dillard University and the Hampton Institute (now Hampton University). The inspiration for much of her artwork came from the Black southern experience, the Civil Rights struggle, and her own inner experience.

In a 2004 painting titled “Barrier”, Lewis explains “She’s trying to get out of a hole, and that big white barrier –its a man– is blocking her. It has to do with segregation.”

Her advocacy for black art was unparalleled. She created many avenues to expand its reach including publishing books via her own publishing company, Contemporary Crafts Gallery, spearheading The National Conference of Artists, and creating and distributing Black Art: An International Quarterly, later known as the International Review of African American Art.

_____________

That sentiment struck a chord for me. As enjoyable as I find visiting museums and viewing Black art, I am often uncomfortable with the curators’ statements about the work. Black art rarely dwells inconspicuously in a gallery. Usually, it is accompanied by excessive fanfare and used as a progressive benchmark for largely white-washed museums and galleries. I’ve started to call it “Strong Black Art”. Like the trope of the “Strong Black Woman”, Strong Black Art is supernaturally equipped. Its seeming intention within the gallery is all at once to humanize Black people, celebrate Black talent–though never exalt it to the pinnacle of the masters– and confront anti-Black racism, but in a resilient, non-threatening manner.

The legacy of slavery and loss of African indigenous roots does necessitate the documentation of the richness of Black American history, art, and culture. Samella Lewis’ work and contributions have undoubtedly paved the way for popular and rising Black American artists of today. Recent high-profile art created by Black artists, such as President Obama’s official portrait artist, Kehinde Wiley and the rising appointment of Black curators are ushering more Black viewers into museums and galleries and hopefully helping to change the landscape. In 2020, The New York Times profiled nine Black artists who understand the “white gaze”, but refuse to center it.

“I realized very quickly”, said Amy Sherald, the artist responsible for former First Lady Michelle Obama’s official portrait, “once I crossed into painting the black figure, that we are a political statement in and of ourselves, especially when we’re hanging on the walls of museums and institutions. Because of that, I knew I didn’t want the work to be marginalized any further, and I didn’t want the conversation to be solely about identity or politics–our images deserve more than that.”

Quotes from:

Photo Credit: College Art Association (CAA)