On a fall night in 1992, I crossed Pennington Road in my neighborhood to drop off a homework assignment to one of my high school best friends, Jamie.

Jamie is a white girl, and the road that split our two neighborhoods split two different experiences of race and class in our hometown of Ewing, New Jersey. My side was mostly mixed with Black and white families and largely middle class. But if you cross Pennington Road to Jamie’s side, you immediately step into a different world — one that was both lower and middle-class working whites of Irish and Italian descent.

Earlier that year, there were stories in the local paper about Black kids having bottles thrown at them by white guys at Pennington’s local bars, as the kids passed through the neighborhood minding their business.

On this particular night around Halloween, I passed homes in those neighborhoods, noticing TV-flickery through their windows like the ones on my block. After placing the work in Jamie’s mailbox, I made my way back home– but before I could get to the top of the block where home was in sight, racing red and blue lights flashed brightly around me. A police cruiser had pulled up.

Within seconds two officers got out and threw me face-down on the hood of the cruiser. I could feel my heart beating against the idle engine as they took my bookbag, name, and dignity.

With my face turned sideways on the hood of the car, it heated up with pain and shame. I stealthily looked back-and-forth and watched as several families peered from their windows or stood on their porches, watching me get patted down. I bit my lip hard enough to cry and when they let me go, my bookbag spilled open like a busted lip. I went home but never mentioned my experience to my mother. I was convinced I’d done something wrong.

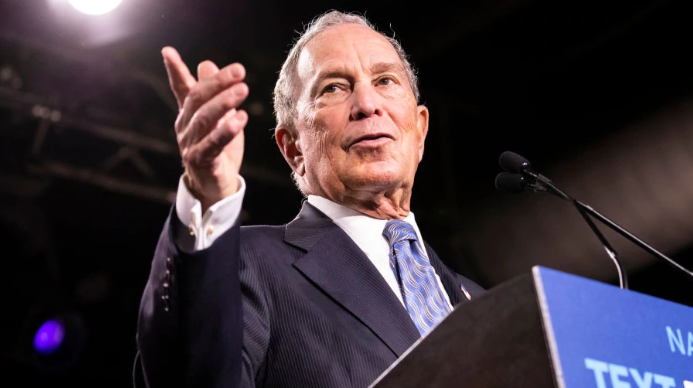

In Mike Bloomberg’s New York City, that sort of practice was law, thanks to his stop-and-frisk policy during his tenure as mayor. Now as Bloomberg seeks the Black vote, perfectly timed with his pursuit of the Democratic nomination, he’s also seeking to rewrite his legacy.

After a catastrophic reign with stop-and-frisk that disproportionally policed Black and Brown people at a rate nine times greater than whites, Bloomberg has had this to offer: I’m sorry.

This sort of artful, soulless apologizing has frequently been at the heart of white American politics. It has been part and parcel of law-and-order tactics that haven’t been limited to one political party affiliation nationally (Nixon and the Clintons) or locally (like Chicago’s Rahm Emmanuel).

It’s a part of a predictable campaign appeal to Black voters who have lived through and endured these policies. And it’s an appeal to white voters who likely are comforted by the “out of sight, out of mind” use of these policies, but also wooed by the “goodness” and “reflection” that politicians like Bloomberg get to use at the expense of Black bodies.

The Black church, which has been America’s cultural courtroom of convenience when it suits public figures, was naturally one of the stops for Bloomberg’s “I’m sorry” express. Last year he visited Christian Cultural Center in Brooklyn; a megachurch whose congregation was all too familiar with what Bloomberg’s policing meant to many of them.

He was peak contrite; an odd choice for a man that only a year ago criticized presidential hopefuls Joe Biden and Beto O’Rourke for enacting the same type of apology tours. He didn’t understand why his progress should be stopped and scrutinized on the basis of his identity. Ironic.

As he stood before the Christian Cultural Center’s congregation though, he offered contrition:

“I now see that we should have acted sooner, and acted faster,” said Bloomberg.

This week, video footage from 2015 was released showing Bloomberg addressing a crowd at the Aspen Institute, defending his stop-and-frisk policies, saying he was ok with Black and Latino kids being “…throw(n) up against the wall…” and that their high arrest rates for possessing marijuana and not guns, was only natural because the neighborhoods where these kids were was “where all the crime is.”

It would be easy for Bloomberg’s fans to dismiss or couch these comments; they’re now five years old and he is now on the same apology tour that he himself despised only 11 months ago. “He’s changed, learned and is growing,” and “looking to make things right for his past ills,” is the likely response. But the restoration process for Bloomberg requires just giving him a little more power: he was mayor of New York City before, and now we’re being asked to help make him President of the United States.

Black America and the Black American vote is fed up with these sorts of pivots, but the Democratic party still doesn’t get it. Nearly the entire slate of this election’s Democratic candidates have been asked to be accountable for their particularly anti-black policies and actions.

Pete Buttigieg, Kamala Harris, Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders, and Cory Booker have all had to clarify their stances and positions both past and present. But the only reparation that they offer is one of rhetoric, and increasingly that’s proving to not be enough.

The Black vote is often represented as a monolithic block of people to be catered to as if we’re a mindless morass of unsophistication or political diversity. It’s meant that we’ve spent campaign season watching a familiar dance. In this renewed season of Black scrutiny, everyone can get it. These are the types of things that don’t even require deep receipts; we can readily see the stagnation on Black attainment by nearly every metric possible post-Civil Rights.

The political apology is supposed to suffice the anger and misgivings the Black community might have, when our newest “champions” (and firmly solely white Democratic candidates now that Andrew Yang has dropped out), step up and ask for one more chance.

But should we be so quick to forgive and accept? Increasingly, Black America is trying to find the lie. Which Bloomberg is the real Bloomberg? The one that stands before a Black congregation in Brooklyn saying, “I was wrong and I am sorry?” Or is it the one that spoke a couple of years ago, comfortable in a roomful of elites talking unapologetically about restoring order by creating disorder for the innocent?

His messaging often stays so trained on the careful balance of acknowledging an apology but then going into a redirection – like when Bloomberg appeared on CBS in an interview with Gayle King. There, he said, as he was grilled by King on his regret and the timing with his presidential run: “I apologize. Let’s go fight the NRA and find other ways to stop the murders and incarceration. Those are the things that I’m committed to do.”

But those words aren’t any meaningful admission. It’s classic misdirection and one that doesn’t take any ownership around the core issues of the type of racist and aggressive policy action that stop-and-frisk is really about. Bloomberg, who as recently as early 2019 was defending his legacy as a stop-and-frisk mayor, is playing a tried and true game of empty apologizing.

For all their proclaimed love for Black people, it seems that few candidates have anything aspirational for Black voters. And yet, they are supposed to be our heroes; their greatest extension and offer to us being reflections, epiphanies, and apologies.

But this story isn’t just about the typical way that politicians seek to rewrite the history of their political and policy errors. The fact of the matter seems to be that they lie. They lie and they ask us to not only forgive and forget but to love them all over again. To give them a second chance not with our vote, but with our lives.

We are in an era of broken legacies that need to be mended and addressed. Black America is this nation’s abused, jilted lover. We’ve been beaten, broken, lied to, lifted up and knocked back down again.

These apologies aren’t about apologizing for anything; they’re really about asking for Black people to transcend our pain and serve a higher purpose in the name of the country, or, in this case, Bloomberg.

Like that day I was thrown down on the hood of a police car, my cheek still burns with the lies we’ve been told for our own good.

Story credit to Tre Johnson/The Grio.

Photo credit to The Grio.