African-American History Honor

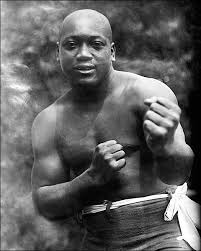

Jack Johnson

In the world of sports, African-Americans represent well, especially when it comes to making history. Most of these history makers were able to accomplish this duing times when it sports were restricted to African-Americans, therby making it a constant struggle, because not only were they battling an opponent on the field, they were also doing so off the field and basically, in society.

In Major League Baseball, it was Jackie Robinson who became the first African-American to play in the sport in 1947. When he signed his contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers, he knew he was about to face tremendous scruntiny from teammates, the opposing team and fans across the country. Still, Robinson endured it all and won the National League Rookie of the Year Award that season. A Year later, he led his team to the World Series and eventually won the National League Most Valuable Player Award in 1949. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1962.

African-Americans have also represented well in boxing. Great names such as Joe Louis, Muhammad Ali, Larry Holmes and others have dominated the sport, won several belts and represented as boxing’s standard from generation to generation. But before those gentleman made it into the ring, there was one who paved helped pave the way for them to display their talents in the sport. That man was Jack Johnson, who was the first African-American to become the first Heavyweight Boxing Champion.

Born March 31, 1878 in Galveston Texas, Johnson was born the third child of nine, and the first son, of Henry and Tina “Tiny” Johnson, two former slaves who worked blue collar jobs as a janitor and a dishwasher to support their children and put them through school. His father Henry served as a civilian teamster of the Union’s 38th Colored Infantry, and was a role model for his son.

Although Jack grew up in the South, he said that segregation was not an issue in the somewhat secluded city of Galveston, as everyone living in Galveston’s 12th Ward was poor and went through the same struggles. Johnson remembers growing up with a “gang” of white boys, in which he never felt victimized or excluded.

His biggest challenge as a child was at the age of 12 when he was confronted by a boy who hit him on the jaw. About to run away from the quarrel Johnson remembers Grandma Gilmore, or his mother, who told him, “Arthur, if you do not whip Willie, I shall whip you”. After winning the fight, Johnson developed a new mentality, and toughness to carry with him through his life.

After Johnson quit attending school, he eventually got a job tending horses. He stuck with this job until he would find a new apprenticeship for a carriage painter by the name of Walter Lewis. Lewis, who had a passion for boxing, enjoyed watching friends spar, and although boxing was somewhat new to Johnson, he began to learn how to hit hard and strong. Johnson later claimed that it was thanks to Lewis that he would become a boxer.

After returning home for a short period of time, Johnson once again left at the age of 16, this time heading for Manhattan. While in Manhattan, Jack found living arrangements with Joe Walcott, a welterweight fighter from the West Indies. Once again Johnson found work exercising horses for the local stable, until he was fired for exhausting a horse. Soon finding employment as a janitor for a gym owned by German born heavyweight fighter, Herman Berneau, Johnson eventually put away enough for two pairs of boxing gloves, sparring every chance he got. Throughout his time in Manhattan, living with Walcott and working for Berneau, Johnson began to develop his unique style of fighting which would make him famous.

Johnson made his debut as a professional boxer on November 1, 1898 in Galveston, Texas when he knocked out Charley Brooks in the second round of a 15-round bout for what was billed as “The Texas State Middleweight Title”. In his third pro fight on May 8, 1899, he battled “Klondike” (John W. Haynes), an African American heavyweight known as “The Black Hercules”, in Chicago. Klondike, who had declared himself the “Black Heavyweight Champ”, won on a technical knockout (TKO) in the fifth round of a scheduled six-rounder. The two fighters met again in 1900, with the first contest resulting in a draw as both fighters were on their feet at the end of 20 rounds. Johnson won the second fight by a TKO when Klondike refused to come out for the 14th round. Johnson however, did not claim Klondike’s unrecognized title.

Johnson won his first title on February 3, 1903, beating Denver Ed Martin on points in a 20-round match for the World Colored Heavyweight Championship. Johnson held the title until it was vacated when he won the world heavyweight title from Tommy Burns in Sydney, Australia on Boxing Day 1908. His reign of 2,151 days was the third longest in the 60-year-long history of the colored heavyweight title.

Johnson’s journey to the World Heavyweight Boxing Championship was a tough one because world heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries refused to face him then. Black boxers could meet white boxers in other competitions, but the world heavyweight championship was off limits to them, but he finally won the world heavyweight title on December 26, 1908 after beating the reigning world champion, Canadian Tommy Burns, in Sydney, Australia.The fight lasted fourteen rounds before being stopped by the police in front of over 20,000 spectators. The title was awarded to Johnson on a referee’s decision.

But there was a greater fight that took place outside of the ring as racial animosity among whites ran so deep that it was called out for a “Great White Hope” to take the title away from Johnson. While Johnson was heavyweight champion, he was covered more in the press than all other notable black men combined. The lead-up to the bout was peppered with racist press against Johnson. Even the New York Times wrote of the event, “If the black man wins, thousands and thousands of his ignorant brothers will misinterpret his victory as justifying claims to much more than mere physical equality with their white neighbors.” As title holder, Johnson thus had to face a series of fighters each billed by boxing promoters as a “great white hope,” often in exhibition matches. But through it all, Johnson kept fighting. In 1909, he beat Tony Ross, Al Kaufman, and the middleweight champion Stanley Ketchel.

In 1910, former undefeated heavyweight champion James J. Jeffries came out of retirement to challenge Johnson. He had not fought in six years and had to lose well over 100 pounds to get back to his championship fighting weight. Initially Jeffries had no interest in the fight, but those who wanted to see Johnson defeated badgered Jeffries mercilessly for months, and offered him an unheard sum of money, reputed to be about $120,000 to which he finally acquiesced. Racial tension was brewing leading up to the fight and to prevent any harm to either boxer, guns were prohibited within the arena as was the sale of alcohol or anyone under the effects of alcohol. Behind the racial attitudes being instigated by the media was a major investment in gambling for the fight with 10-7 odds in favor of Jeffries. It was known as the ‘Fight of the Century.’

The fight took place on July 4, 1910 in front of 20,000 people, at a ring built just for the occasion in downtown Reno, Nevada. Jeffries proved unable to impose his will on the younger champion and Johnson dominated the fight. By the 15th round, after Jeffries had been knocked down twice for the first time in his career, Jeffries´ corner threw in the towel to end the fight and prevent Jeffries from having a knockout on his record. The “Fight of the Century” earned Johnson $65,000 and silenced the critics, who had belittled Johnson’s previous victory over Tommy Burns as “empty,” claiming that Burns was a false champion since Jeffries had retired undefeated.

The outcome of the fight triggered race riots that evening—the Fourth of July—all across the United States, from Texas and Colorado to New York and Washington, D.C. Johnson’s victory over Jeffries had dashed white dreams of finding a “great white hope” to defeat him. Many whites felt humiliated by the defeat of Jeffries.

Blacks, on the other hand, were jubilant, and celebrated Johnson’s great victory as a victory for racial advancement. In all, riots occurred in more than 25 states and 50 cities. Twenty people were killed across America from the riots, and hundreds more were injured.

On April 5, 1915, Johnson lost his title to Jess Willard, a working cowboy from Kansas who started boxing when he was twenty-seven years old. With a crowd of 25,000 at Oriental Park Racetrack in Havana, Cuba, Johnson was knocked out in the 26th round of the scheduled 45 round fight. Johnson, although having won almost every round, began to tire after the 20th round, and was visibly hurt by heavy body punches from Willard in rounds preceding the 26th round knockout. After losing his world heavyweight championship, Johnson never again fought for the colored heavyweight crown.

Just like the athletes of today, Johnson was an early example of the celebrity athlete in the modern era, appearing regularly in the press and later on radio and in motion pictures. He earned considerable sums endorsing various products, including patent medicines, and indulged several expensive hobbies such as automobile racing and tailored clothing, as well as purchasing jewelry and furs for his wives. In 1920, he opened a night club in Harlem; he sold it three years later to a gangster, Owney Madden, who renamed it the Cotton Club.

Unfortunately, Johnson was looked down upon by the African American community, especially by the black scholar Booker T. Washington who said “It is unfortunate that a man with money should use it in a way to injure his own people, in the eyes of those who are seeking to uplift his race and improve its conditions, I wish to say emphatically that Jack Johnson’s actions did not meet my personal approval and I am sure they do not meet with the approval of the colored race.”

Johnson’s biggest fight was outside the ring as his marriages and relationships-were all to white women. On October 18, 1912, Johnson was arrested on the grounds that his relationship with Lucille Cameron violated the Mann Act against “transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes” due to her being an alleged prostitute and due to Johnson being black. Her mother also swore formally that her daughter was insane. Cameron, soon to become his second wife, refused to cooperate and the case fell apart. Less than a month later, Johnson was convicted by an all-white jury in June 1913, despite the fact that the incidents used to convict him took place before passage of the Mann Act. He was sentenced to a year and a day in prison.

But Johnson skip bail and leave the country, joining Cameron in Montreal on June 25, before fleeing to France. In order to flee to Canada to skip his bail, Johnson posed as a member of a black baseball team. For the next seven years, they lived in exile in Europe, South America and Mexico. Johnson returned to the U.S. on July 20, 1920. He surrendered to Federal agents at the Mexican border and was sent to the United States Penitentiary, Leavenworth to serve his sentence September 1920.

There have been recurring proposals to grant Johnson a posthumous presidential pardon. A bill requesting President George W. Bush to pardon Johnson in 2008, passed the House, but failed to pass in the Senate. On July 29, 2009, Congress passed a resolution calling on President Barak Obama to issue a pardon. A Change.org petition was started by heavyweight champion Mike Tyson. former boxer Mike Tyson. So far, Obama hasn’t pardoned Johnson.

Johnson continued fighting until 1938 at age 60 when he lost 7 of his last 9 bouts, losing his final fight to Walter Price by a 7th-round TKO. On June 10, 1946, Johnson died in a car crash near Franklington, North Carolina a small town near Raleigh, after racing angrily from a diner that refused to serve him. He was taken to the closest black hospital, Saint Agnes Hospital in Raleigh. He was 68 years old at the time of his death.

Johnson was inducted into the Boxing Hall of Fame in 1954, and is on the roster of both the International Boxing Hall of Fame and the World Boxing Hall of Fame. In 2005, the United States National Film Preservation Board deemed the film of the 1910 Johnson-Jeffries fight “historically significant” and put it in the National Film Registry. During his boxing career, Jack Johnson fought 114 fights, winning 80 matches, 45 by knockouts.

At the time of his death, a reporter asked Johnson’t 3rd wife Irene Pineau what she loved about him, she replied “I loved him because of his courage. He faced the world unafraid. There wasn’t anybody or anything he feared.” Spoken like a true champion.

Please e-mail ray at ray@urbanmediatoday.com

Follow him @urbanmediaRay on teitter

Sources: Wikipedia, Washington Post