April 2nd is World Autism Awareness Day

Delays in autism diagnosis may contribute to the high rate of intellectual disability among Black autistic children in the United States, according to a study published today in Pediatrics1.

Such delays mean these children miss out on age-appropriate, autism-specific care and a chance to improve their cognitive skills, the researchers say2.

“This is a very serious outcome, and we’re talking about very serious numbers of people affected by this,” says lead investigator John Constantino, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Until this year, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that a lower proportion of Black children were diagnosed with autism than were children of other races. A report published in March shows that gap has effectively closed3.

But other disparities remain: Among children with intellectual disability, Black children receive an autism diagnosis an average of six months later than white children, according to the March report. And 47 percent of Black autistic children also have intellectual disability, compared with 27 percent of white children.

The new study is a “deep dive” on the role that access to services plays in this disparity, Constantino says.

“We can’t just sit with that if we don’t at least try to see whether some of this can be resolved by leveling the playing the field for diagnosis and access to services,” he says. “There’s almost no excuse.”

Long delays:

The researchers examined the experiences of Black families in the U.S. as they sought a diagnosis and treatment for concerns about a child’s development, language or behavior.

They interviewed the parents of 584 Black children with autism, including 118 girls, and compiled timelines of the families’ experiences, including the developmental outcomes of the autistic children and their siblings.

They found a three-year delay in diagnosis: On average, parents first noted concerns about their child’s development when the child was 23 months old and told a professional six months later, but didn’t receive an autism diagnosis until their child was more than 5 years old.

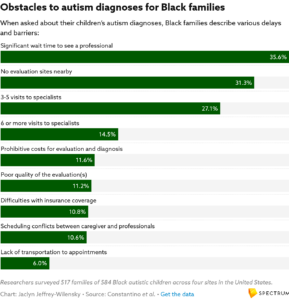

More than a third of the families reported long wait times to see a professional; 14 percent made at least six visits to specialists before their child was diagnosed. Nearly a third said that a lack of available professionals contributed to the diagnostic delay.

The study found no links between the autistic children’s intelligence quotient (IQ) and their family’s income or parents’ education, meaning the increased prevalence of intellectual disability among Black autistic children can’t be attributed to poverty, Constantino says. Poverty, which disproportionately affects Black families in the U.S, is associated with worse cognitive outcomes.

“A simple sort of excuse of saying, ‘Well, that’s the problem of poverty, we can’t fix that,’ is inappropriate,” Constantino says.

There was also no association with gestational age at birth or the extent to which IQ varies among the child’s immediate family members, both of which are linked to low IQ in the general population.

Instead, the results suggest that a lack of access to services at the right time may hold these children back, Constantino says. The study found that the autistic children began receiving some kind of care one to three years prior to an autism diagnosis, suggesting they did not benefit from autism-specific therapies.

The findings serve as a call to action for the research community, says Walter Zahorodny, associate professor of pediatrics at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School in Newark, who was not involved in the work.

“There’s no doubt that African-American children are underserved and receive delayed interventions,” Zahorodny says. “Certainly, that’s something that deserves respect and action.”

Unequal environment:

It’s not clear from the findings that diagnostic delays underlie the increased prevalence of intellectual disability in Black autistic children, other researchers say — particularly given that the CDC’s report shows only a six-month age gap in diagnosis between Black and white children.

“While it’s possible, it also seems speculative,” Zahorodny says. “I don’t think it’s proven that six months’ earlier intervention could make a difference in the intellectual capacity of a child. That’s a stretch, I think.”

Other factors linked to low IQ could also contribute to the disparity, including lead poisoning and quality of nursery schools, says Maureen Durkin, professor of public health at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who was not involved in the research. Some families have reported difficulty getting therapists to visit their homes if they live in a neighborhood perceived as “dangerous,” she says.

“We do need to address all of those,” Durkin says. “I think it’s important to draw attention to this.”

Future research should tease out what creates the environment for racial disparities in care to persist, says Waganesh Zeleke, associate professor of clinical mental health counseling at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, who was not involved in the research. Zeleke’s research has shown that white families of autistic children say they are more satisfied with the healthcare they receive and more likely to contact a professional about concerns than minority families are4.

Many minority children also aren’t screened until they start school, Zeleke says, further delaying the process.

“We’re missing a window that we could intervene or improve,” Zeleke says. “I am glad they pointed it out, named it and addressed it directly. It’s a wakeup call for interventionists to see it and name it for what it is.”

Story Credit: Laura Dattaro

Article originally posted on Spectrum