by Anna Clark and Sarahbeth Maney, Photography by Sarahbeth Maney

This story was originally published by ProPublica. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

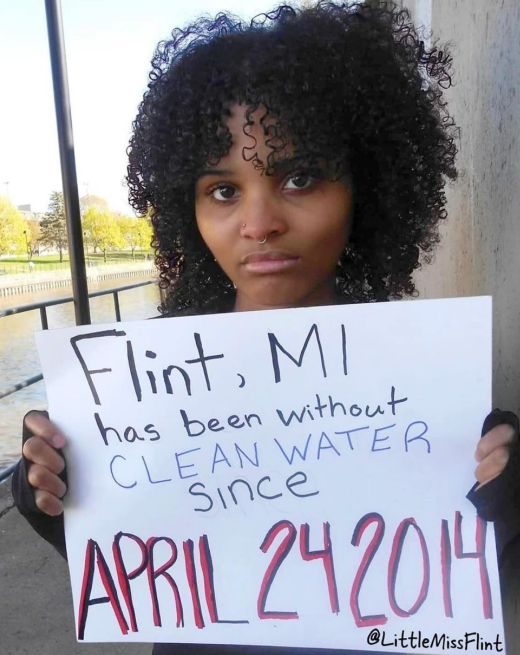

Flint, Michigan, is less than 70 miles from the Great Lakes, the most abundant fresh water on the face of the planet. It’s laced with creeks and a broad river that bears its name. Yet in 2014, Flint’s drinking water became a threat — not because of scarcity, or a natural disaster, or even a familiar tale of corporate pollution.

Ten years ago this spring, public officials made catastrophic changes in the city’s water source and treatment, then used testing practices that hid dangers. As problems emerged, they failed to appropriately change course. Residents raised repeated concerns about the color, odor and taste of the water but struggled to get a sufficiently serious response, especially from state and federal authorities.

It didn’t help that the distressed city was under the authority of state-appointed emergency managers, an unusually expansive oversight system that residents decried. For a crucial period of about 3 1/2 years, local decision-making was not accountable to voters. The result: excess exposure to toxic lead, bacteria and a disinfection byproduct in Flint’s drinking water. An outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease sickened 90 people and killed 12. (The toll is likely higher, as Frontline documented.) The water, now drawn from the Flint River, wasn’t treated with corrosion control — a violation of federal law — so the pipes deteriorated more every day.

At one point, saying the water damaged its machinery, a General Motors plant switched to another community’s system. Flint’s emergency manager and other officials still insisted that nothing was seriously wrong with the water. But if the water was harming machines, many wondered, what was it doing to people?

It took about 18 months, and an extraordinary effort by residents and a few key researchers, before the state reconnected Flint with Detroit’s water, which is drawn from Lake Huron. In the years since, remediation efforts have included replacing corroded pipes, at-home filtration and infrastructure investments, which seem to have yielded promising results. Michigan’s Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy said in December that Flint’s water had met federal standards for more than seven straight years. Recent testing followed Michigan’s requirements, adopted in 2018, which are even tougher than federal standards. The state and city are working to resolve deficiencies to the supply system that can affect water safety.

But no one can flip a switch on public trust. And Flint was vulnerable long before the water crisis.

Many point to the crisis as an extreme example of environmental injustice, where people of color and poor people, and especially those who are both, are disproportionately exposed to toxic conditions. A state commission acknowledged that race and class contributed to Flint not having “the same degree of protection from environmental and health hazards as that provided to other communities. Moreover, by virtue of their being subject to emergency management, Flint residents were not provided equal access to, and meaningful involvement in, the government decision-making process.”

That emergency manager law is still on the books. The work to replace the pipes is mostly done — but the city has blown repeated deadlines to complete it. Two state investigations under two administrations led to high-profile criminal charges, including allegations of involuntary manslaughter, official misconduct and willful neglect of duty. Primarily, state officials and employees were charged, including the former director of the state health agency and the former governor. Two emergency managers were also charged; both pleaded not guilty. One has said there was “overwhelming consensus” for the switch, and he was “grossly misled” by state water experts.

No case made it to trial. A new attorney general’s team dismissed the initial cases and started a new investigation. But the second wave of charges fell apart when courts rejected the use of a one-man grand jury to gain indictments.

The Environmental Protection Agency didn’t use its authority to effectively protect public health in Flint, according to the agency’s inspector general. The EPA has denied liability, however, and earlier this year asked a federal judge to dismiss a lawsuit alleging that it failed to properly intervene.

While it was announced in 2020, not one penny of the class-action settlement of more than $626 million has reached residents. With more than 40,000 claims and 30 compensation categories, a special master indicated recently that the initial review should be complete this summer, but there will still be more vetting to do before claims are paid. (Some lawyers and contractors, though, have already been paid preliminary fees and expenses.)

Water is Flint’s origin story. The city was founded on a riverbank, and water powered its rise. Each spring, the water turns neighborhoods and parks lush. But these days, the betrayal of trust by the very institutions meant to protect residents has made some extra cautious as they look to keep themselves and their community safe. Their relationship with water is forever changed.

McCathern’s church served as a bottled-water distribution site during the crisis, which, he said, strengthened relationships and community trust. But he worries for the next generation, especially their psychological well-being. And he has his own fears too. He said he often smells a “foul odor” from the water. He is apprehensive when showering and usually drinks bottled water, he said, but sometimes lets his guard down to make tea with tap water.

In recent years, McCathern was diagnosed with multiple myeloma cancer. He believes it’s connected to chemicals in the water but will never know for sure. Over his 22 years at Joy Tabernacle, McCathern said, he’s seen an uptick in youth suicide. He wonders about a connection between lead exposure and violence. He recalls sitting at one funeral and thinking, Oh my God, if it produces violent tendencies, that’s not just outward violent tendencies — that’s internal.

An investigation published in Science Advances showed an 8% increase in the number of school-aged children in Flint with a qualified special educational need. But, the researchers indicated, it’s difficult to pinpoint to what extent lead is the direct cause.

A cross-sectional study backed by the federal Office of Victims of Crime found that five years after the onset of the crisis, an estimated 1 in 5 residents — roughly 22,600 people — had met the criteria for clinical depression in the past year. One in 4, or 25,000 people, were estimated to have had post-traumatic stress disorder. According to researchers, only 34.8% of residents were offered mental health services to assist with psychiatric symptoms related to the crisis. Most people used them, if offered.

Medlin said she uses her food stamp benefits on bottled water deliveries from Walmart for Audrina’s bottles. For her first months, Medlin relied on the infant’s father to bathe her at his home outside the city.

Ambitious programs aim to support Flint’s most vulnerable residents. Medlin is enrolled in Rx Kids, which “prescribes” a no-strings-attached payment of $1,500 for pregnant Flint residents and $500 for each month of the baby’s first year. A Medicaid initiative that covers youth up to age 21 and pregnant parents who were exposed to Flint’s water was extended in 2021 for another five years. And the Flint Registry connects people with health services while monitoring the effectiveness of efforts to prevent lead poisoning.

Reynolds is the executive director of a local literacy organization, tutoring children and adults on reading, writing and African American culture. She said her hair began falling out during the water crisis. While she was diagnosed with alopecia, she said, another doctor later told her that the hair loss is likely connected to the water. She too feels like she’ll never know for sure. Because of the lack of information about the water at the time, she didn’t think to track her symptoms.

The water’s effect on hair and skin was among the earliest concerns raised by residents, though a direct correlation has been difficult to prove. A 2016 state and federal analysis — conducted after Flint switched back to Detroit’s system — identified nothing in the current water supply that affected hair loss. A survey of more than 300 residents by academic researchers found that more than 40% of respondents said they experienced hair loss beyond what they considered normal before the crisis. Black respondents reported significantly higher percentages of hair loss. The more physical symptoms respondents reported, the more likely they were to report psychological symptoms.

Having taught and tutored Flint families for decades, Reynolds feels the weight of the community’s unmet needs.

Nearly 80,000 people now live in Flint, according to recent census data, a drop of about 20% in the past 10 years. Fifty-seven percent are Black, 34% are white and 4% are Hispanic. Median household income is $33,036. Nearly 38% are in poverty. Population loss and disinvestment make it difficult to maintain a water system, with fewer people paying for infrastructure designed for a much larger city.

Flint had almost 200,000 residents in 1960; it built water infrastructure to support 50,000 more, according to the city’s communications director. It connected to Detroit’s system in the first place because it expected continued growth. Vacancy can worsen water quality because water sits longer in pipes before reaching a tap — a problem made visible when metals from corroding pipes saturated the water more in some Flint neighborhoods than in others.

In addition to service-line replacement efforts, the city offers free filters to residents. Beyond legally mandated testing, a unique community water lab provides residents with a free way to learn about their water. Young people lead much of the work. As lab director and Flint City Council member Candice Mushatt put it, “We’re training the next generation to be prepared in a way that we were not.”

Results range from 0.031 parts per billion up to over 50 ppb of lead from water samples tested in Flint, according to Mushatt. Under federal law, if a community water system reaches 15 ppb of lead, based on the 90th percentile of samples, certain public health measures must be taken. No amount of lead is safe.

Flint residents have emphasized the importance of determining for themselves when justice has been done. In a 2020 paper, a cohort of community advocates wrote that they expect accountability, policy reform and community-driven investments. “And we will be insisting,” they wrote, “as always, that people ask us and our fellow residents before concluding that Flint has been made whole.”