RALEIGH — Spend a little time with Jannet Barnes, and it becomes clear that closing health gaps and overcoming socioeconomic disparities sometimes just comes down to opening your mouth and letting people know what you need.

And when children are the ones hanging in the balance, amplifying voices turns up the volume for little people who haven’t figured out how to speak for themselves.

“Exactly,” Barnes said.

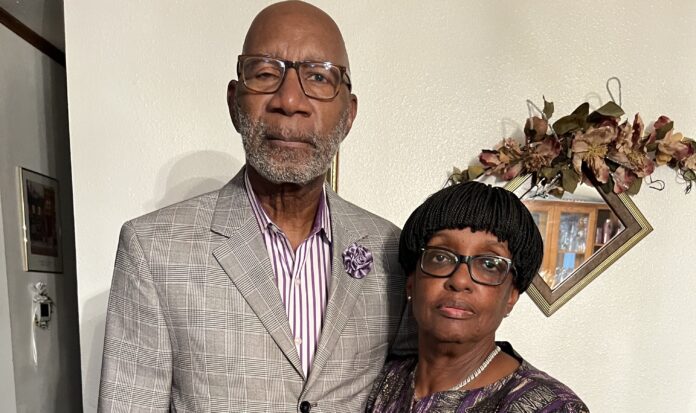

She and her husband, James, opened their Knightdale home to four foster kids. The children were siblings who never were under the same roof. The two girls would go to one foster home, the boys to another. James and Jannet adopted them.

But it’s not like Barneses had an empty nest.

“I had four of my own, but the Lord told us to do this,” Jannet said.

Project REFOCUS, an acronym for racial ethnic framing of community-informed and unifying surveillance, was established to address racism and social stigma related to COVID 19 and other crises. It’s a national effort funded by the CDC Foundation and is co-led by the Howard University Department of Communication, Culture and Media Studies and the UCLA Center for the Study of Racism, Social Justice and Health. Wake County is one of six locations for Project REFOCUS pilot projects. Other locations include Phillips County in Detroit, Michigan; Albany, Georgia; San Antonio, Texas; and the Bronx in New York.

COVID-19 wasn’t a thing back in the 1980s when James and Jannet brought the four siblings into their home. But the way the couple saw needs and met them gets at the Shaw University Project REFOCUS team’s holistic approach to addressing disparities.

“It’s only through advocating for those who don’t have a voice or whose voices aren’t heard that we will change the challenges with disparities in our community, whether they’re health disparities or economic disparities” said Bettie Murchison, who leads the community advisory board for Raleigh’s Project REFOCUS effort.

The four siblings arrived at the Barnes’ home at ages 5, 7, 9 and 11. Jannet said folks assumed she had eight biological children, which actually was the desired effect, she said.

“You can’t show me a child that asked to be born,” Jannet said.

So Jannet treated her adopted kids as if she birthed them. It was the equitable thing to do, and that’s the way to not just close the gap on disparities but prevent them in the first place, she explained.

It was practical things like pushing against the clothing allocation for foster children. At the time, each child was assigned a $150 voucher that had to be used at Walmart, Jannet said. The Barneses understood they’d be setting up their foster children for ridicule at school by having them show up wearing Walmart clothes. Jannet said she fought the system in order to spend the same amount out of pocket at trendier stores and then get reimbursed. She won.

Very innovative, Murchison said.

“That’s exactly what we need right now. We need people that aren’t afraid to challenge the status quo,” Murchison said. “You’ve got to have the nerve to say, ‘We’re not gonna take this. This is not who we are. We can do better, and I’ve got a way to do it.’”

The Barneses understood their foster children wanted straight teeth like all of the other kids at school. James and Jannet made it happen.

“All four of them were in braces at the same time,” Jannet said.

The Barneses didn’t pay for those braces, by the way. Jannet opened her mouth, advocated for what the kids needed and got the system to pay for it.

“Paid for all four of them to get their braces,” Jannet said.

That’s Jannet, Murchison said.

“She’s very forward-thinking in that respect. And just because she challenged them — she challenged the status quo — she was able to get some resolution for what she saw as a problem,” Murchison said.

The foster children were behind academically when they arrived in Knightdale. Jannet found tutoring at Roberts Park and Shaw University.

“These are human beings,” Jannet said about her foster children. “They want to be productive, and they want to be supported.”

Which is how societal gaps get closed, because all of the advocacy by the Barneses had everything to do with disparities in health — mental health, Murchison explained.

“It relates to your mental state of mind,” Murchison said. “Children don’t need much to really find a way to demean another child, and that leads to suicidal thoughts. It leads to destructive behavior. It leads to them not wanting to go to school every day.

“All of this has to do with your mental health, your mental state of mind.”

Another key to preventing and overcoming disparities as it relates to foster children is keeping the biological parents connected to the extent possible, Jannet said.

“My philosophy and belief is Mom is gonna always be Mom,” Jannet said. “I don’t care how bad Mama is, Mama is gonna always be Mama.”

Jannet said all four adopted children are doing well.

Source: John McCann, Project REFOCUS