by Jennifer Berry Hawes, photography by Sarahbeth Maney

This story was originally published by ProPublica. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

In the rural community of Wilcox County, Alabama, a Black principal is working to empower students in the segregated public high school. A Black woman is grappling with demons of the county’s past. A white woman is digging into that history. A white high school graduate is realizing the importance of interracial friendships. Others are using art to bridge divides.

ProPublica is examining the lasting effects of “segregation academies,” private schools that opened across the Deep South in opposition to desegregation. In our first story, we wrote about how the local academy in Wilcox is nearly all white while the public schools are virtually all Black. As a result, people don’t often know one another well. When we asked local residents how often they have ever invited someone of another race over for dinner, we heard variations of, “That would be very uncommon.”

Although people haven’t often forged those deeper relationships, we met many who said they want to. We met others who are already doing so.

They confront a long and painful legacy of racism. They battle the inertia of “the way things are.” And they must build trust across racial divides where it often hasn’t existed before.

Shelly Dallas Dale

Shelly Dallas Dale still has flashbacks to being sprayed with tear gas, especially that first time.

Dale was 16 years old in 1971 when she joined a march in downtown Camden, 40 miles south of Selma in the heart of Alabama’s Black Belt, to protest its segregated schools. She and 428 others were arrested for “illegal marching.” They included 87 students. In an article about the march, the local newspaper called them “deluded blacks.”

Dale had grown up afraid of white people, but she still summoned her courage to join the Civil Rights Movement as it unfolded in Camden — even though protestors had lost their jobs and faced violence and arrests.

Before the desegregation march, she had become so fearful for her safety that she wrote her own obituary. Then she went to her older sister with a request. “This is the dress,” she recalled saying. “If I should get killed, bury me in it.”

At the march, someone fired tear gas at her. A white man shot her younger sister, she said, the bullet rocketing across the girl’s back just beneath the skin. But Dale and her family remained determined that Black students in Wilcox County should have access to the same educational opportunities as white children. She would march again — and face tear gas again.

Dale went on to become the county’s long-serving (and first female) tax assessor, a role that brought her into contact with every type of person — including the white people who had traumatized her and other Black children.

She tried to face her fear each day. She said she got to know people beyond the flashbacks and the years of fighting for basic rights like voting and school equality.

“I think it has helped me to embrace people more,” she said. “And to look beyond the evil side.”

Betty Anderson

Unlike many Black residents of Wilcox County during the 1950s and 1960s, Betty Anderson’s father did not work for a white man. For more than four decades, Joe Anderson ran the Camden Shoe Shop in the heart of downtown. Because he was his own boss, he joined local actions in the Civil Rights Movement without the fear for his livelihood that others, including sharecropping families, faced.

When his health declined in 2006, Betty Anderson moved back to help him. She had spent 42 years away, including a stint modeling in New York, but quickly became a fixture again in Wilcox County.

To honor her father and other family members, she opened the Camden Shoe Shop & Quilt Museum in his old building. The sidewalk leading up to it is painted shades of rose, azure and forest green. A pillow embroidered with “Welcome” sits on the arm of an old chair adorned with flowers. Inside its colorful doors awaits an array of artwork and historical memorabilia, much of it from her own relatives.

Her whole family was involved in the Civil Rights Movement. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. visited their home. Activists stayed with them. Her grandmother and other family living in nearby Gee’s Bend made quilts to earn money for demonstrators’ gas and other needs.

The museum features quilts made by her great-great-grandmother, who had been enslaved and passed the craft down to later generations. Her father’s 1965 voting card and his 1967 NAACP membership card are on display. So are the jeans and a shoe Anderson herself wore in the historic 1965 march from the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma to the state capital of Montgomery, Alabama, 54 miles away. Her Converse — black with a red stripe — has two golf-ball-sized holes worn into its sole.

Anderson marched again for voting rights in Camden a few weeks later with classmates from her school. Although Wilcox County was mostly Black, virtually none of its registered voters were. Police arrested her middle brother. They jailed her youngest brother, just 8 years old, in Selma. For hours, nobody knew where he was.

Despite the pain she lived through, Anderson is one of the people in Camden who seems to know everyone in town — Black and white. An upbeat and gregarious woman, she has no qualms crossing racial lines and is a frequent presence at activities held by both Black and white residents. She opens her eclectic museum as a local gathering spot.

Frequent visitors include the women who work in the nearby Black Belt Treasures Cultural Arts Center. Anderson is an artist in residence there, but the organization means much more to her. In a town where white and Black neighbors remain apart in many ways, she and the white women who run it have become close friends.

Black Belt Treasures

When Black Belt Treasures launched in 2005, one goal rose above others: Its founders wanted to craft a new narrative, one that had gone largely untold in a region often defined by poverty and need.

To do this, they wanted to draw people off the interstate and into Alabama’s Black Belt — particularly Camden, in the heart of it — to see for themselves.

“We have gotten so much negative press and yet there’s a richness of life here,” Executive Director Sulynn Creswell said. “We have problems, but there are many, many talented, gifted people who live in this region.”

Among other things, Black Belt Treasures operates a gallery in a former car dealership that is now filled with paintings and pottery and quilts fashioned by hundreds of artists from across the region. Its staffers also work with tourism efforts and take myriad arts programs out into schools and the broader community.

Creswell and the center’s other employees have been key players in revitalizing downtown Camden, including playing a role in the creation of a colorful “Revolution of Joy” mural on a building between their gallery and Betty Anderson’s museum. All of their names are painted on it, along with those of a diverse group of people from around the county who came together to add their own artistic touches. Creswell and Kristin Law, who directs the center’s art programs and marketing, also were founding members of a local racial reconciliation group. The women, who are white, emphasized that they want the community to come together more — and they see the arts as a prime vehicle for that.

“Yes, we have had our bad history,” Law said. “But we are also a beautiful place with beautiful people, and we’re all trying to work together to make a better place.”

That includes two teenagers who work with them. Jazmyne Posey is a Black student at the local public high school. While working in the gallery, she met and befriended Law’s daughter, Samantha Cook, who is white and attends Wilcox Academy, the local private school. The other key women on staff here also have sent their children to the academy.

In a town that is otherwise still segregated, especially in its schools, the two teenagers forged a friendship that likely would never have happened if they had relied on their school encounters.

Susan McIntyre

In 1975, a few years after the private Wilcox Academy opened in Camden when schools were being desegregated, a young white woman named Susan McIntyre took a job there.

During her 12 years teaching French, she admired the school’s instruction and met families whose ancestors had owned plantations in the area. She sent her two daughters to the school and became close friends with another white woman whose children were about the same age.

Back then, it was unheard of, she said, for a Black student to attend the academy, and none did. After growing up in a white world, she didn’t think much about why.

Later, she took a job teaching in the county’s mostly Black public schools, where she still works. She interacted with Black students and teachers far more than ever before in her life.

One day, while watching a group of Black students, a thought struck her. She wondered what message generations of school segregation had sent them. It was, she feared, an unjust lesson of inferiority.

She began to read every book she could find in the local library about slavery. She dug into the ways desegregation played out in Wilcox County — and how it continues to affect students. It was hard to ignore the role Wilcox Academy had played in the continued segregation of students.

“This is the thing that’s haunted me for years,” she said. “What if we had never started the private school?”

The public schools in Wilcox County remain nearly all Black. But in recent years, a few Black students have crossed the county’s racial divide to enroll at the academy.

Anna Crosswhit

In August 2020, McIntyre’s granddaughter Anna Crosswhite was about to start her junior year at Wilcox Academy when she volunteered to be a water girl for the football team. One day, she noticed four Black students watching practice. Recognizing a couple of them from her brother’s summer baseball league, she walked over to say hello.

The guys explained that COVID-19 had shut down the public school’s football season. As upperclassmen, they didn’t want to miss their last years of high school sports and they were thinking of applying to the academy.

Crosswhite, who is white and has an adopted brother from China, was excited about the prospect of the academy’s student body becoming more diverse.She only knew of one Black student at the school. And with just 23 students in her class, she liked the possibility of new friends.

She also thought back to when she was younger and volunteered at BAMA Kids Inc., a local nonprofit. Once in a while, she heard Black youth volunteers say things like, “Girl, we’re not allowed at your school.” Maybe the new students would help change that perception.

But old notions lingered. She said she heard pushback from other academy students, although she didn’t want to divulge details that would identify her classmates.

“We were 50 years behind,” she said. “I didn’t realize how behind we were.”

The academy admitted the football players, and Crosswhite said she became friends with them. Although they hung out on the weekends and often went out to eat together, she never went into any of their homes. But she got to know them far better than she would have if they hadn’t gone to school together.

Now a student at Auburn University, she is studying to become a teacher and sees how those friendships better prepared her for what she calls “the real world.”

Principal Curtis Black

When a bell blared at Wilcox Central High School one morning this spring, the principal slipped from behind his desk beneath a stuffed deer head with blue school baseball caps propped on its antlers.

Curtis Black emerged into a hallway filled with students who, like him, grew up in a segregated school. Not a single white student attended the one he went to in a neighboring county. He realized the detriments of isolating students this way when he arrived at college and encountered a wider variety of people.

Due to population decline in Wilcox County, the school operates in a building far bigger than its student body of about 400 can fill. Where once the county had three public high schools, it now has just this one. When the centralized school opened in this building near downtown Camden, complete with a competition-size swimming pool, many hoped it offered what white parents wanted — and that they might give it a chance.

That didn’t happen. But Black carefully avoided criticizing Wilcox Academy. Instead, he rattled off programs that his school offers. Students can access the high school’s medical-training lab, its agriculture lab, its welding lab. They can take dual credit courses with area community colleges. They can earn certifications.

As principal, he wants to create broader opportunities for his students, many of whom descend from people who were enslaved in this area. Their grandparents were traumatized by violent reactions to the Civil Rights Movement. His goals include exposing them more to the outside world and providing them the academic tools to land quality jobs out of high school or to succeed in college.

This spring, walking down the school’s hallways, he pointed to the senior class.

“In two or three months, they’re going to be around people from different backgrounds, different ethnic groups, different Christian groups,” Black said. “So we need that exposure.”

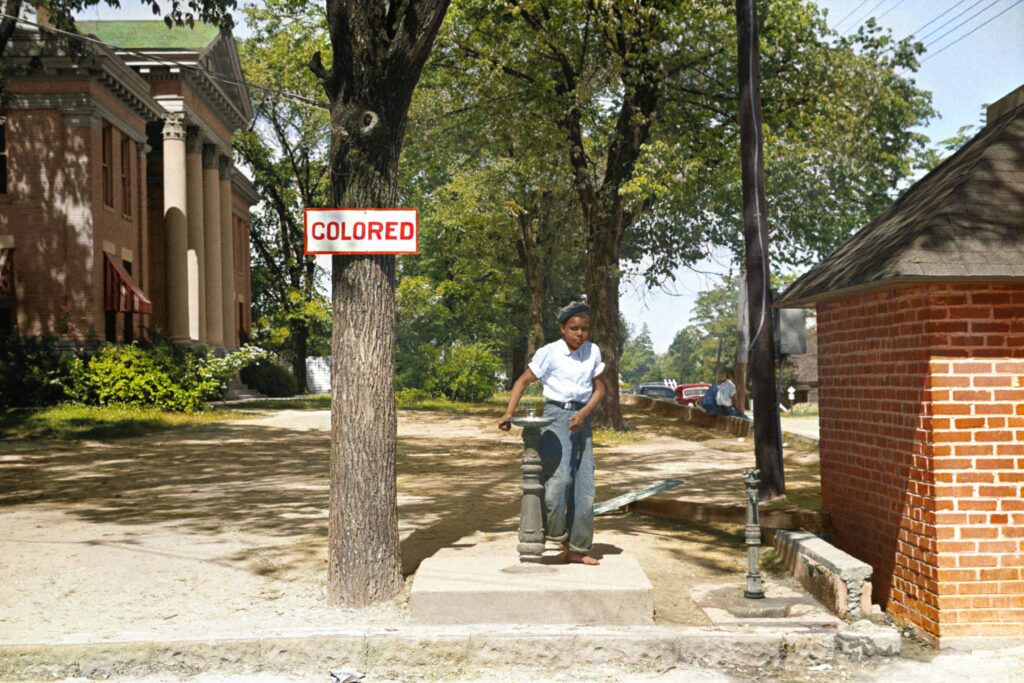

Image: Unseen Histories/Unsplash