by Jennifer Berry Hawes, photography by Gavin McIntyre for ProPublica

This story was originally published by ProPublica. ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Sitting at her bedroom desk, nursing a cup of coffee on a quiet Tuesday morning, Lauren Davila scoured digitized old newspapers for slave auction ads. A graduate history student at the College of Charleston, she logged them on a spreadsheet for an internship assignment. It was often tedious work.

She clicked on Feb. 24, 1835, another in a litany of days on which slave trading fueled her home city of Charleston, South Carolina. But on this day, buried in a sea of classified ads for sales of everything from fruit knives and candlesticks to enslaved human beings, Davila made a shocking discovery.

On page 3, fifth column over, 10th advertisement down, she read:

“This day, the 24th instant, and the day following, at the North Side of the Custom-House, at 11 o’clock, will be sold, a very valuable GANG OF NEGROES, accustomed to the culture of rice; consisting of SIX HUNDRED.”

She stared at the number: 600.

A sale of 600 people would mark a grim new record — by far.

Until Davila’s discovery, the largest known slave auction in the U.S. was one that was held over two days in 1859 just outside Savannah, Georgia, roughly 100 miles down the Atlantic coast from Davila’s home. At a racetrack just outside the city, an indebted plantation heir sold hundreds of enslaved people. The horrors of that auction have been chronicled in books and articles, including The New York Times’ 1619 Project and “The Weeping Time: Memory and the Largest Slave Auction in American History.” Davila grabbed her copy of the latter to double-check the number of people auctioned then.

It was 436, far fewer than the 600 in the ad glowing on her computer screen.

She fired off an email to a mentor, Bernard Powers, the city’s premier Black history expert. Now professor emeritus of history at the College of Charleston, he is founding director of its Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston and board member of the International African American Museum, which will open in Charleston on June 27.

If anyone would know about this sale, she figured, it was Powers.

Yet he too was shocked. He had never heard of it. He knew of no newspaper accounts, no letters written about it between the city’s white denizens.

“The silence of the archives is deafening on this,” he said. “What does that silence tell you? It reinforces how routine this was.”

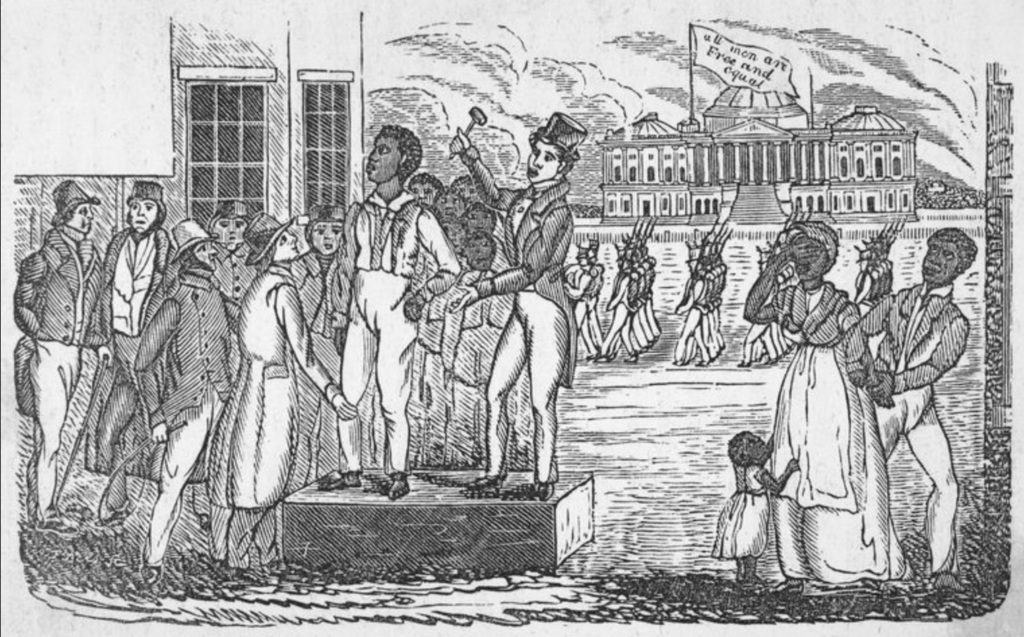

The auction site rests between a busy intersection in downtown Charleston and the harbor that ushered in about 40% of enslaved Africans hauled into the U.S. In that constrained space, Powers imagined the wails of families ripped apart, the smells, the bellow of an auctioneer.

When Davila emailed him, she also copied Margaret Seidler, a white woman whose discovery of slave traders among her own ancestors led her to work with the college’s Center for the Study of Slavery to financially and otherwise support Davila’s research.

The next day, the three met on Zoom, stunned by her discovery.

“There were a lot of long pauses,” Davila recalled.

It was March 2022. She decided to announce the discovery in her upcoming master’s thesis.

A year later, in April, Davila defended that thesis. She got an A.

She had discovered what appears to be the largest known slave auction in the United States and, with it, a new story in the nation’s history of mass enslavement — about who benefited and who was harmed by such an enormous transaction.

But that story initially presented itself mostly as a great mystery.

The ad Davila found was brief. It yielded almost no details beyond the size of the sale and where it was being held — nothing about who sent the 600 people to auction, where they came from or whose lives were about to be uprooted.

But details survived, it turned out, tucked deep within Southern archives.

In May, Davila shared the ad with ProPublica, the first news outlet to reveal her discovery. A reporter then canvassed the Charleston newspapers leading up to the auction — and unearthed the identity of the rice dynasty responsible for the sale.

The Ball Dynasty

The ad Davila discovered ran in the Charleston Courier on the sale’s opening day. But ads for large auctions were often published for several days, even weeks, ahead of time to drum up interest.

A ProPublica reporter found the original ad for the sale, which ran more than two weeks before the one Davila spotted. Published on Feb. 6, 1835, it revealed that the sale of 600 people was part of the estate auction for John Ball Jr., scion of a slave-owning planter regime. Ball had died the previous year, and now five of his plantations were listed for sale — along with the people enslaved on them.

The Ball family might not be a household name outside of South Carolina, but it is widely known within the state thanks to a descendant named Edward Ball who wrote a bestselling book in 1998 that bared the family’s skeletons — and, with them, those of other Southern slave owners.

“Slaves in the Family” drew considerable acclaim outside of Charleston, including a National Book Award. Black readers, North and South, praised it. But as Ball explained, “It was in white society that the book was controversial.” Among some white Southerners, the horrors of slavery had long gone minimized by a Lost Cause narrative of northern aggression and benevolent slave owners.

Based on his family’s records, Edward Ball described his ancestors as wealthy “rice landlords” who operated a “slave dynasty.” He estimated they enslaved about 4,000 people on their properties over 167 years, placing them among the “oldest and longest” plantation operators in the American South.

John Ball Jr. was a Harvard-educated planter who lived in a three-story brick house in downtown Charleston while operating at least five plantations he owned in the vicinity. By the time malaria killed him at age 51, he enslaved nearly 600 people including valuable drivers, carpenters, coopers and boatmen. His plantations spanned nearly 7,000 acres near the Cooper River, which led to Charleston’s bustling wharves and the Atlantic Ocean beyond.

ProPublica reached out to Edward Ball, who lives in Connecticut, to see if he had come across details about the sale during his research.

He said that 25 years ago when he wrote “Slaves in the Family,” he knew an enormous auction followed Ball Jr.’s death, “and yet I don’t think I contemplated it enough in its specific horror.” He saw the sale in the context of many large slave auctions the Balls orchestrated. Only a generation earlier, the estate of Ball Jr.’s father had sold 367 people.

“It is a kind of summit in its cruelty,” Ball said of the auction of 600 humans. “Families were broken apart, and children were sold from their parents, wives sold from their husbands. It breaks my heart to envision it.”

And it gets worse.

After ProPublica discovered the original ad for the 600-person sale, Seidler, the woman who supported Davila’s research, unearthed another puzzle piece. She found an ad to auction a large group of people enslaved by Keating Simons, the late father of Ball Jr.’s wife, Ann. Simons had died three months after Ball Jr., and the ad announced the sale of 170 people from his estate. They would be auctioned the same week, in the same place, as the 600.

That means over the course of four days — a Tuesday through Friday — Ann Ball’s family put up for sale 770 human beings.

In his book, Edward Ball described how Ann Ball “approached plantation management like a soldier, giving lie to the view that only men had the stomach for the violence of the business.” She once whipped an enslaved woman, whose name was given only as Betty, for not laundering towels to her liking, then sent the woman to the Work House, a city-owned jail where Black people were imprisoned and tortured.

A week before the first auction ad appeared for Ball Jr.’s estate, a friend and business adviser dashed off a letter urging Ann Ball to sell all of her late husband’s properties and be freed of the burden. “It is impossible that you could undertake the management of the whole Estate for another year without great anxiety of mind,” the man wrote in a letter preserved at the South Carolina Historical Society.

Ball did what she wanted.

On Feb. 17, the day her husband’s land properties went to auction, she bought back two plantations, Comingtee and Midway — 3,517 acres in all — to run herself.

A week later, on the opening day of the sale of 600 people, she purchased 191 of them.

More Than Names

In mid-March 1835, the auction house ran a final ad regarding John Ball Jr.’s “gang of negroes.” It advertised “residue” from the sale of 600, a group of about 30 people as yet unsold.

Ann Ball bought them as well.

Given she bought most in family groups, her purchase of 215 people in total spared many traumatic separations, at least for the moment.

As she picked who to purchase, she appears to have prioritized long-standing ties. Several were elderly, based on the low purchase price and their listed names — Old Rachel, Old Lucy, Old Charles.

Many names included on her bills of sale also mirror those recorded on an inventory of John Ball Jr.’s plantations, including Comingtee, where he and Ann had sometimes lived. Among them: Humphrey, Hannah, Celia, Charles, Esther, Daniel, Dorcas, Dye, London, Friday, Jewel, Jacob, Daphne, Cuffee, Carolina, Peggy, Violet and many more.

Most of their names are today just that, names.

But Edward Ball was able to find details about at least one family Ann Ball purchased. A woman named Tenah and her older brother Plenty lived on a plantation a few miles downriver from Comingtee that Ball Jr.’s uncle owned.

Edward Ball figured they came from a family of “blacksmiths, carpenters, seamstresses and other trained workers” who lived apart from the field hands who toiled in stifling, muddy rice plots. Tenah lived with her husband, Adonis, and their two children, Scipio and August. Plenty, who was a carpenter, lived next door with his wife and their three children: Nancy, Cato and Little Plenty.

When the uncle died, he left Tenah, Plenty and their children to John Ball Jr. The two families packed up and moved to Comingtee, then home to more than 100 enslaved people.

Life went on. Tenah gave birth to another child, Binah. Adonis tended animals in the plantation’s barnyard.

Although the families were able to stay together, they nonetheless suffered under enslavement. At one point, an overseer wrote in his weekly report to Ball Jr. that he had Adonis and Tenah whipped because he suspected they had butchered a sheep to add to people’s rations, Edward Ball wrote in his book.

After her husband’s death, Ann Ball’s purchase appears to have kept the two families together, at least many of them. The names Tenah, Adonis, Nancy, Binah, Scipio and Plenty are listed on her receipt from the auction’s opening day.

Yet, hundreds more people who remained for sale from the Ball auction likely “ended up in the transnational traffic to Mississippi and Louisiana,” said Edward Ball, now at work on a book about the domestic slave trade.

He noted that buyers attending East Coast auctions were mostly interstate slave traders who transported Black people to New Orleans and the Gulf Coast, then resold them to owners of cotton plantations. In the early 1800s, cotton had taken over from rice and tobacco as the South’s king crop, fueling demand at plantations across the lower South and creating a mass migration of enslaved people.

Birth of Generational Wealth

Although the sale of 600 people as part of one estate auction appears to be the largest in American history, the volume itself is hardly out of place on the vast scale of the nation’s chattel slavery system

Ethan Kytle, a history professor at California State University, Fresno, noted that the firm auctioning much of Ball’s estate — Jervey, Waring & White — alone advertised sales of 30, 50 or 70 people virtually every day.

“That adds up to 600 pretty quickly,” Kytle said. He and his wife, the historian Blain Roberts, co-wrote “Denmark Vesey’s Garden,” a book that examines what he called the former Confederacy’s “willful amnesia” about slavery, particularly in Charleston, and urges a more honest accounting of it.

Slavery was a form of mass commerce, he said. It made select white families so wealthy and powerful that their surnames still form a sort of social aristocracy in places like Charleston.

Although no evidence has surfaced yet about how much the auction of 600 people enriched the Ball family, the amount Ann Ball paid for about one-third of them is recorded in her bills of sale buried within the boxes and folders of family papers at the South Carolina Historical Society. They show that she doled out $79,855 to purchase 215 people — a sum worth almost $2.8 million today.

The top dollar she paid for a single human was $505. The lowest purchase price was $20, for a person known as Old Peg.

Enslaved people drew widely varied prices depending on age, gender and skills. But assuming other buyers paid something comparable to Ann Ball’s purchase price, an average of $371 per person, the entire auction could have netted in the range of $222,800 — or about $7.7 million today — money then distributed among Ball Jr.’s heirs, including Ann.

They weren’t alone in profiting from this sale. Enslaved people could be bought on credit, so banks that mortgaged the sales made money, too. Firms also insured slaves, for a fee. Newspapers sold slave auction ads. The city of Charleston made money, too, by taxing public auctions. These kinds of profits helped build the foundation of the generational wealth gap that persists even today between Black and white Americans.

Jervey, Waring & White took a cut of the sale as well, enriching the partners’ bank accounts and their social standing.

Although the men orchestrated auctions to sell thousands of enslaved people, James Jervey is remembered as a prominent attorney and bank president who served on his church vestry, a “generous lover of virtue,” as the South Carolina Society described him in an 1845 resolution. A brick mansion in downtown Charleston bears his name.

Morton Waring married the daughter of a former governor. Waring’s family used enslaved laborers to build a three-and-a-half story house that still stands in the middle of downtown. In 2018, country music star Darius Rucker and entrepreneur John McGrath bought it from the local Catholic diocese for $6.25 million.

Alonzo J. White was among the most notorious slave traders in Charleston history. He also served as chairman of the Work House commissioners, a role that required him to report to the city fees garnered from housing and “correction” of enslaved people tortured in the jail.

“Yet, these men were upheld by high society,” Davila said. “They are remembered as these great Christian men of high value.” After John Ball Jr. died, the City Council passed a resolution to express “a high testimonial of respect and esteem for his private worth and public services.”

But for the 600 people sold and their descendants? Only a stark reminder of how America’s entrenched racial wealth gap was born, Davila said, with repercussions still felt today.